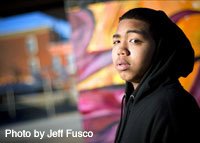

Sole Survivor: Jerry Dang, one year later

This story was published in the Philadelphia Weekly in the March 8- 14 issue.

This story was published in the Philadelphia Weekly in the March 8- 14 issue.EVER SINCE his grandmother was mugged around the corner from their South Philadelphia home in early February, Jerry Dang wakes up early and walks the 69-year-old woman to the corner at 6 a.m. He waits until her bus safely picks her up, shuttling her to work, about an hour ride from their home.

Then the 14-year-old returns to his quiet row home and prepares for school. He walks into the dim, empty living room where, on March 13, 2005, he found his 10-year-old brother stabbed to death on the couch and his lifeless 6-year-old sister lying face down in the corner. He eats breakfast in the kitchen where, on that night, he watched his distraught mother plunge a knife into her belly and collapse on the floor.

After school Jerry tries to stay out of the house. He avoids thinking about the horrible things he saw. He hangs out at the local rec center or plays pickup football games on the asphalt basketball court until dark.

His grandmother Bach Dang, a tiny Vietnamese immigrant who speaks little English, returns from work late in the day, and the two dine together, usually eating Vietnamese food she prepares.

Jerry's mother and siblings are gone. He never knew his father. His grandmother is the only family he has left.

"The only reason I'm still here is because of my grandma," Jerry says in a low, soft voice that's barely audible. "If it wasn't for her, I probably wouldn't be in school. I'd probably be getting in trouble."

•

Jerry and his family were in the news for less than 24 hours last year.

Hours after being woken by his brother Kenny's piercing cries at 2 o'clock that Sunday morning, Jerry had TV cameras and reporters in his face, asking what had happened.

He stood in the doorway of his South Bancroft Street home and somberly told the media how he was asleep in his bedroom he shared with his little brother. He heard screams, went downstairs, found Kenny dead on the couch, and saw his sister Mimi crumpled on the linoleum floor. His 37-year-old mother Thuy Dang was sitting on the floor crying, covered in blood.

Jerry said he reached for her, but he said she told him, "I can't help you anymore."

And she fatally stabbed herself.

"Her face changed," Jerry said last year. "She dropped to the ground and started shaking. Then it was over."

Police corroborated Jerry's story that his mother, whom he said had suffered from depression and had attempted suicide before, killed both children and then took her own life.

A few hours before Jerry lost most of his family, 9-year-old Walder DeJesus was killed by a stray bullet as he sat innocently in his father's minivan in North Philadelphia. Who shot the boy remained a mystery for several days. DeJesus' death, one of 18 murders that week, captured the headlines and airtime over the following days.

One day after Jerry's life was forever altered, the media moved on to other stories.

In the end Kenny and Mimi Dang were just two of the 380 murders during the violent year. His mother was just a suicide.

•

Just to be safe, Jerry didn't watch TV for about two weeks after the deaths, he says. He didn't look at newspapers.

He and his stepfather, who has since moved to Florida, had to clean the bloody mess inside the home.

"It was painful," Jerry says.

After the bodies were cremated, they donated all of Kenny's and Mimi's possessions to charity.

Pictures of his mother, brother and sister now rest on a makeshift Buddhist shrine in Jerry's home. They sit on a mauve brocaded tablecloth, surrounded by offerings of flowers, fruit, milk, water and potato chips. His mother is smiling in the photograph, and Jerry says he prays to her every day.

"I tell her I miss her," he says demurely.

Jerry attended weekly services for his family at the Chua Bo De Buddhist Temple, but he stopped going in January. He also visited a free community therapist for a while, but he quit in October.

He doesn't even like to think about what happened that morning a year ago on Monday.

"When I start thinking, I go to the basement and start lifting," he says.

Jerry is a big, barrel-chested, half-Vietnamese, half-African-American kid who towers over his grandmother. His baby-fat-filled cheeks that were so prominent last year are starting to vanish.

He dreams of being a professional football player, a tight end or defensive back. And he knows he'd need a scholarship to play in college, because otherwise, he couldn't afford it. He played on South Philadelphia High School's junior varsity squad last fall but quit midseason.

"I got too busy," he says.

Nearly every day after school Jerry runs around the basketball court at the DiSilvestro Recreation Center, smiling and laughing with friends in uninhibited joy. The small playground is his sanctuary. When he's not playing football or shooting hoops, he talks to the younger kids in the after-school program inside the center.

"I really try to give him love," says Theresa Williams, the center's supervisor.

Most of the young people in the neighborhood, largely occupied by African-Americans and immigrants from Southeast Asia, know what happened to Jerry's family, Williams says.

"He doesn't talk about it," she says, even though Kenny and Mimi used to spend time at the playground as well. Kenny helped plant the garden there a few years ago. "He seems to have taken on the role of the man, taking care of his grandmother and all."

If something would happen to her, Jerry knows what his fate would be.

"I'd be up for adoption," he mumbles.

•

On Sunday Jerry and his grandmother will return to the temple for a memorial service. Without his siblings, he's lonely, he says. But he doesn't hold any grudges against his mother.

"I don't really worry about that anymore," Jerry says. "It's in the past now. I can't do anything about it."